Paul Whybrow

Full Member

I've been raving about the crime writing of Walter Mosley on the Colony, and I also enjoyed his writing guide This Year You Write Your Novel.

It's a short book of less than 25,000 words, aimed at newbie authors, but any writer would benefit from his common sense advice. It has the welcome qualities of not only offering useful tips, but being encouraging in an arm-around-the-shoulder way, as well as gently cajoling you to just get on with writing the words.

One section of the second chapter, The Elements of Fiction, startled me when I first read it, until I realised how astute Mosley's advice is:

Maybe your character gets up out of bed and walks across the room to the mirror. You need her to see the bags under her eyes and lines on her aging face. That's good. But in order to have us feel what it is to get up out of that bed, we might want to add a little more: the sound of the sheets falling to the floor; the urge to urinate, which the protagonist resists to see what time and life have wrought upon her visage; the grit beneath her bare feet on the floor; the pain in her left knee that has been with her since a time, years ago, when she twisted her ankle on a stone stairway while attending her mother's funeral—the mother whom she now very much resembles. Every one of these details tells and also shows us something about our protagonist and/ or her world.

Most of these details are pedestrian. Why, you might ask, would we want to make the experiences of our characters ordinary? Because everyday experiences help the reader relate to the character, which sets up the reader's acceptance of more extraordinary events that may unfold.

If your audience believes in the daily humdrum physical and emotional experiences of your characters, then your readers will believe in those character's reality and thus can be taken further.

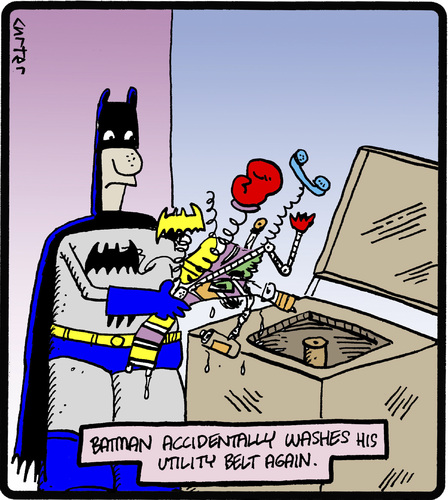

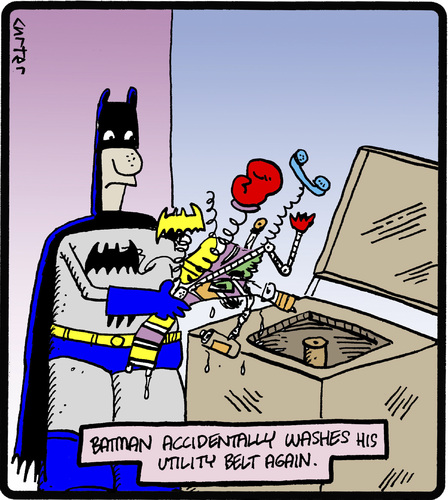

Even a rugged superhero facing a confrontation with an evil mastermind, will have everyday needs and preoccupations, which, when mentioned make them three-dimensional, rather than a cardboard cutout representing the forces of justice.

As writers, we're constantly advised to polish our sentences, paragraphs and chapters—and it's always recommended that less is more—but, terse brilliance may mean eliminating, (or not even thinking of), the obvious. Even famous authors do this, so focused on the plot, that they forget to mention their protagonist needs to eat or sleep, and that he should have a few bruises after being beaten senseless in an alleyway in the previous chapter.

Sometimes, not a lot happens action-wise, but your characters still have thoughts and interact with people. These situations allow for pedestrian writing that add valuable elements to the story. In my Cornish Detective series, I always have a chapter where the protagonist detective meets with his best friend, a forensic pathologist, at an Indian restaurant. This device allows me to explore my hero's private life, for his older friend has offered him wise counsel and he opens up to her.

By letting readers into the mind of a multi-faceted copper, showing his strengths and weaknesses, I hope to engender loyalty. His doubts and dreams are similar to those of the readers; he's an ordinary man doing an extraordinary job, and showing how he navigates through everyday tasks adds realism as well as offering opportunities for plot developments.

In one of my novels, the detective protagonist visited the supermarket, on his way back from searching for the corpse of a murder victim whose head had been placed atop a road sign. As he parked, he spotted a heavily-scarred thug he fancied for the killing, who was peacefully sat on a park bench watching a song thrush sing against the backdrop of purple storm clouds. He went across to chat with him—getting useful insights into how a violent man thinks.

My detective remembered to go and buy his chamomile tea, thus returning to a pedestrian activity after a frisson of excitement.

However, too much detail of the mundane can be a bad thing. I've just given up on reading a novel set in the world of art theft, as perpetrated by the Mafia, who use valuable paintings as currency and collateral. Located in Florence, which was described in painstaking detail as the private investigator trudged around, when he wasn't eating restaurant meals or consuming the contents of the minibar in his hotel room. All that happened in 200 pages was pedestrian writing and I lost interest. I started to despise the protagonist, who appeared to be lost in a tourist guide. While slogging through it, I was reminded of Mark Twain's observation:

The test of any good fiction is that you should care something for the characters; the good to succeed, the bad to fail. The trouble with most fiction is that you want them all to land in hell, together, as quickly as possible.

There should be a name for the sense of satisfaction that comes when a jaded reader gives up on a tiresome book.

Do you incorporate ordinary everyday events into your stories?

Are your characters fallible in little ways? Frailties are a good way of generating empathy from the reader.

It's a short book of less than 25,000 words, aimed at newbie authors, but any writer would benefit from his common sense advice. It has the welcome qualities of not only offering useful tips, but being encouraging in an arm-around-the-shoulder way, as well as gently cajoling you to just get on with writing the words.

One section of the second chapter, The Elements of Fiction, startled me when I first read it, until I realised how astute Mosley's advice is:

the pedestrian in fiction

Maybe your character gets up out of bed and walks across the room to the mirror. You need her to see the bags under her eyes and lines on her aging face. That's good. But in order to have us feel what it is to get up out of that bed, we might want to add a little more: the sound of the sheets falling to the floor; the urge to urinate, which the protagonist resists to see what time and life have wrought upon her visage; the grit beneath her bare feet on the floor; the pain in her left knee that has been with her since a time, years ago, when she twisted her ankle on a stone stairway while attending her mother's funeral—the mother whom she now very much resembles. Every one of these details tells and also shows us something about our protagonist and/ or her world.

Most of these details are pedestrian. Why, you might ask, would we want to make the experiences of our characters ordinary? Because everyday experiences help the reader relate to the character, which sets up the reader's acceptance of more extraordinary events that may unfold.

If your audience believes in the daily humdrum physical and emotional experiences of your characters, then your readers will believe in those character's reality and thus can be taken further.

Even a rugged superhero facing a confrontation with an evil mastermind, will have everyday needs and preoccupations, which, when mentioned make them three-dimensional, rather than a cardboard cutout representing the forces of justice.

As writers, we're constantly advised to polish our sentences, paragraphs and chapters—and it's always recommended that less is more—but, terse brilliance may mean eliminating, (or not even thinking of), the obvious. Even famous authors do this, so focused on the plot, that they forget to mention their protagonist needs to eat or sleep, and that he should have a few bruises after being beaten senseless in an alleyway in the previous chapter.

Sometimes, not a lot happens action-wise, but your characters still have thoughts and interact with people. These situations allow for pedestrian writing that add valuable elements to the story. In my Cornish Detective series, I always have a chapter where the protagonist detective meets with his best friend, a forensic pathologist, at an Indian restaurant. This device allows me to explore my hero's private life, for his older friend has offered him wise counsel and he opens up to her.

By letting readers into the mind of a multi-faceted copper, showing his strengths and weaknesses, I hope to engender loyalty. His doubts and dreams are similar to those of the readers; he's an ordinary man doing an extraordinary job, and showing how he navigates through everyday tasks adds realism as well as offering opportunities for plot developments.

In one of my novels, the detective protagonist visited the supermarket, on his way back from searching for the corpse of a murder victim whose head had been placed atop a road sign. As he parked, he spotted a heavily-scarred thug he fancied for the killing, who was peacefully sat on a park bench watching a song thrush sing against the backdrop of purple storm clouds. He went across to chat with him—getting useful insights into how a violent man thinks.

My detective remembered to go and buy his chamomile tea, thus returning to a pedestrian activity after a frisson of excitement.

However, too much detail of the mundane can be a bad thing. I've just given up on reading a novel set in the world of art theft, as perpetrated by the Mafia, who use valuable paintings as currency and collateral. Located in Florence, which was described in painstaking detail as the private investigator trudged around, when he wasn't eating restaurant meals or consuming the contents of the minibar in his hotel room. All that happened in 200 pages was pedestrian writing and I lost interest. I started to despise the protagonist, who appeared to be lost in a tourist guide. While slogging through it, I was reminded of Mark Twain's observation:

The test of any good fiction is that you should care something for the characters; the good to succeed, the bad to fail. The trouble with most fiction is that you want them all to land in hell, together, as quickly as possible.

There should be a name for the sense of satisfaction that comes when a jaded reader gives up on a tiresome book.

Do you incorporate ordinary everyday events into your stories?

Are your characters fallible in little ways? Frailties are a good way of generating empathy from the reader.