Paul Whybrow

Full Member

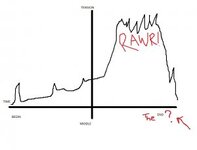

I've read conflicting advice about how a narrative arc should flow in a novel. I was delighted when I found a graph that showed how a story should have highs and lows, as well as longueurs when nothing much seems to be happening, and that the psychological thriller novel that I wrote in 2014 'The Perfect Murderer' conformed to it. This was quite by chance, or maybe having read thousands of novels rubbed off on me.

See : http://www.musik-therapie.at/PederHill/Structure&Plot.htm

This approved pattern starts slowly, as my first chapter does, before climbing steeply to an early dramatic peak - which happens in my second chapter when the corpse of an American tourist is found. My third chapter pulls the key police personnel together in a meeting to discuss the case, which shows something of their individual characteristics.

The problem with this, is that if one is submitting just the first three chapters to an agent or publisher, then it's not going to grab them by the lapels and say "look at this !" Some experts advise that the opening paragraph should be shocking, and that the story should hit the ground running with the first chapter charging into the second. One way around this, is to have two versions of your opening chapters - a sensational, make-an-impression sizzler for submissions and the real more sedate bookish form. Daft isn't it ?

I've not done this (yet!), but have used a tip to use a hook/elevator pitch in the first paragraph of my covering letter by describing my novel as The Silence of The Lambs meets World of Warcraft. This is meant to indicate the contrast in how an undetected murderer,a psychopath and The Watcher, a game-playing fantasist approach killing their victims.

In the submissions that I've made to literary agents, and those publishers with an open submission window, I've placed the elevator pitch in the introduction of my query letter. I noticed that the illustrious Redhammer Management, run by AgentPete, had a stipulation in their onsite submission form that the plot be summarised in 250 characters. This had me frothing at the mouth for a moment, until I realised that it forced me to use my elevator pitch.

There's a bewildering variety of formats requested by agents for submissions, and certainly no such thing as an industry standard form. Some ask for the first three chapters, others the first 5,000 or 10,000 words and one asked for the first twenty-five chapters. The most sensible, to my mind, requested three consecutive chapters from anywhere in the novel which I thought best represented my style and the action in the story.

I've read on various forums and blogs that there is a trend towards shorter story formats, owing to readers using iPhones and tablets on the move, where content is taken in bite-sized chunks. Increasingly limited attention spans and the need for instant gratification is also affecting how patient people are when beginning a book - hence the advice that a story should go BOOM right from the start.

I understand the need for a compelling hook or an unique selling point to attract readers, but am really confused about the contradiction between allowing a story to develop with peaks,plateaus and even the odd trough and attempting to provide 0ne cheap thrill after another. No one can stay permanently high, forever aroused and unfailingly interested.

Thoughts please...

See : http://www.musik-therapie.at/PederHill/Structure&Plot.htm

This approved pattern starts slowly, as my first chapter does, before climbing steeply to an early dramatic peak - which happens in my second chapter when the corpse of an American tourist is found. My third chapter pulls the key police personnel together in a meeting to discuss the case, which shows something of their individual characteristics.

The problem with this, is that if one is submitting just the first three chapters to an agent or publisher, then it's not going to grab them by the lapels and say "look at this !" Some experts advise that the opening paragraph should be shocking, and that the story should hit the ground running with the first chapter charging into the second. One way around this, is to have two versions of your opening chapters - a sensational, make-an-impression sizzler for submissions and the real more sedate bookish form. Daft isn't it ?

I've not done this (yet!), but have used a tip to use a hook/elevator pitch in the first paragraph of my covering letter by describing my novel as The Silence of The Lambs meets World of Warcraft. This is meant to indicate the contrast in how an undetected murderer,a psychopath and The Watcher, a game-playing fantasist approach killing their victims.

In the submissions that I've made to literary agents, and those publishers with an open submission window, I've placed the elevator pitch in the introduction of my query letter. I noticed that the illustrious Redhammer Management, run by AgentPete, had a stipulation in their onsite submission form that the plot be summarised in 250 characters. This had me frothing at the mouth for a moment, until I realised that it forced me to use my elevator pitch.

There's a bewildering variety of formats requested by agents for submissions, and certainly no such thing as an industry standard form. Some ask for the first three chapters, others the first 5,000 or 10,000 words and one asked for the first twenty-five chapters. The most sensible, to my mind, requested three consecutive chapters from anywhere in the novel which I thought best represented my style and the action in the story.

I've read on various forums and blogs that there is a trend towards shorter story formats, owing to readers using iPhones and tablets on the move, where content is taken in bite-sized chunks. Increasingly limited attention spans and the need for instant gratification is also affecting how patient people are when beginning a book - hence the advice that a story should go BOOM right from the start.

I understand the need for a compelling hook or an unique selling point to attract readers, but am really confused about the contradiction between allowing a story to develop with peaks,plateaus and even the odd trough and attempting to provide 0ne cheap thrill after another. No one can stay permanently high, forever aroused and unfailingly interested.

Thoughts please...