Paul Whybrow

Full Member

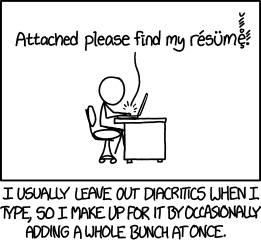

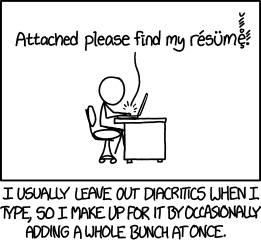

Perhaps I should start the PPPP—Pedantic Paul's Punctuation Patrol, after previously posting about disappearing dots and praiseworthy semicolons, but I've noticed another trend affecting the squiggles that we use to show the nature of a word. Diacritical marks or glyphs indicate how a word is meant to be pronounced, changing the sound of the letter which has the accent mark. In an increasingly bland world, where dumbing-down has triumphed, it's refreshing to see something that offers both accuracy and a stylistic flourish.

Thus the double dot of the diaeresis over the letter in naïve indicates that it should be said as if it were a double e (ny-EEV). Most books print the word as naive—which could be pronounced as nave—it's strange how removing these foreign punctuation marks requires extra knowledge on the part of the reader...it's complicated the reading process, rather than simplified it.

Other common examples are cliché which is often written as cliche, and café usually becomes cafe.

I read a fair few foreign novels in translation, and I've noticed that in these diacritical marks tend to be retained, whereas books published in English-speaking countries omit them—even if the plot takes place abroad where they're used.

Scandinavian novels are replete with diacritical marks, though this doesn't stop British and American publishers from altering even an author's name...presumably to make them look less foreign (and intimidating). A good example of this is hugely successful crime writer Jo Nesbø from Norway, whose surname is usually printed without the slashed o. His name should be pronounced as nez-bOO...rather than nez-bOW.

Other author names that cause confusion are Irish novelist Colm Tóibín (CULL-um Toe-BEAN), fantasy author China Miéville (mee-AY-vill) and French erotic writer Anaïs Nin (Ahn-EYE-ees).

I'm fond of diacritical marks, using them when writing, even though it means pausing for a moment to insert them via the Special Character function in my LibreOffice Writer software.

It's probable that book publishers have their own policy in handling such glyphs, but for the moment, I'll continue to use them. Of course, in the language of their origin, diacritical marks appear on the keyboard...and in the written alphabet, they're usually treated as separate letters and listed after Z.

One that I'm particularly fond of, which has largely disappeared in written English, is a glyph created by merging two letters into what's known as a ligature. This makes Æ or æ a dipthong—an amusing word for a gliding vowel—a combination of two vowel sounds in one syllable. I first encountered it, when studying Latin as a teenager (it was that sort of school ), and it's still commonly used in modern Scandinavian languages. These days, æ usually gets typed as two separate letters, though pleasingly it does remain in Encyclopædia Britannica.

), and it's still commonly used in modern Scandinavian languages. These days, æ usually gets typed as two separate letters, though pleasingly it does remain in Encyclopædia Britannica.

The French, who actively do everything that they can to preserve their nation's identity, have been anxious about relaxed rules about spelling, that sees the disappearance of the circumflex (for example, Août meaning August) as being acceptable practice.

The curious incident of the disappearing French circumflex

Do you use glyphs or diacritical marks in writing your stories?

Have you invented your own...for fantasy or science-fiction?

Do you like seeing such marks printed in a book you're reading, or do they irritate you?

Thus the double dot of the diaeresis over the letter in naïve indicates that it should be said as if it were a double e (ny-EEV). Most books print the word as naive—which could be pronounced as nave—it's strange how removing these foreign punctuation marks requires extra knowledge on the part of the reader...it's complicated the reading process, rather than simplified it.

Other common examples are cliché which is often written as cliche, and café usually becomes cafe.

I read a fair few foreign novels in translation, and I've noticed that in these diacritical marks tend to be retained, whereas books published in English-speaking countries omit them—even if the plot takes place abroad where they're used.

Scandinavian novels are replete with diacritical marks, though this doesn't stop British and American publishers from altering even an author's name...presumably to make them look less foreign (and intimidating). A good example of this is hugely successful crime writer Jo Nesbø from Norway, whose surname is usually printed without the slashed o. His name should be pronounced as nez-bOO...rather than nez-bOW.

Other author names that cause confusion are Irish novelist Colm Tóibín (CULL-um Toe-BEAN), fantasy author China Miéville (mee-AY-vill) and French erotic writer Anaïs Nin (Ahn-EYE-ees).

I'm fond of diacritical marks, using them when writing, even though it means pausing for a moment to insert them via the Special Character function in my LibreOffice Writer software.

It's probable that book publishers have their own policy in handling such glyphs, but for the moment, I'll continue to use them. Of course, in the language of their origin, diacritical marks appear on the keyboard...and in the written alphabet, they're usually treated as separate letters and listed after Z.

One that I'm particularly fond of, which has largely disappeared in written English, is a glyph created by merging two letters into what's known as a ligature. This makes Æ or æ a dipthong—an amusing word for a gliding vowel—a combination of two vowel sounds in one syllable. I first encountered it, when studying Latin as a teenager (it was that sort of school

The French, who actively do everything that they can to preserve their nation's identity, have been anxious about relaxed rules about spelling, that sees the disappearance of the circumflex (for example, Août meaning August) as being acceptable practice.

The curious incident of the disappearing French circumflex

Do you use glyphs or diacritical marks in writing your stories?

Have you invented your own...for fantasy or science-fiction?

Do you like seeing such marks printed in a book you're reading, or do they irritate you?