- Feb 3, 2024

- LitBits

- 0

New blog post by Claire G

Plotting

I’ve watched some great webinars on plotting recently and I thought I’d compile what I’ve learned, as much for myself as for anyone else who might find this info useful

The Four Cornerstones of Plot

Together, the Four Cornerstones Add Up to…

CHANGE!

A satisfying narrative arc portrays how protagonists change internally over time as a result of their choices. This change must be difficult – it must have cost the character something/involved a sacrifice/the ‘death’ of their former self. It must be irreversible. The change can be ‘heroic’ or ‘tragic’ (but a sub-plot/minor character’s change may be the opposite of the main plot/character’s change). Notably, the antagonist usually fails to change, and this is ultimately their most fatal flaw, whereas the protagonist’s eventual ability to change is their strength. A final point to emphasise is that the personal change/redemption matters more than the external/‘outer world’ resolution.

The Bestseller Code (Archer and Jockers)

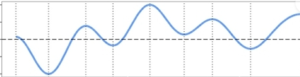

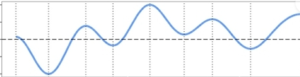

The authors analysed the vocabulary of bestsellers, focusing on the words used to describe characters’ internal states (‘good’ times versus ‘bad’ times resulting from events). They concluded that a key commonality was regular reversals of fortune where turning points force the character to mobilise at the greatest points of conflict, make choices and risk something by making that choice. This is known as the ‘page-turner beat’. The graph shows the protagonist’s fortunes over time when compared to the ‘status-quo’ starting point.

One way to think of this is that the new conflict – resolution – new conflict – resolution sequence equates to the action – reaction – action – reaction sequence, equating to the external – internal – external – internal sequence.

Plot Structures

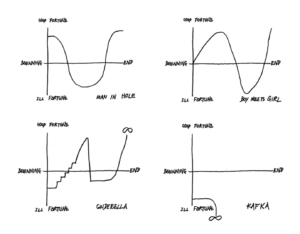

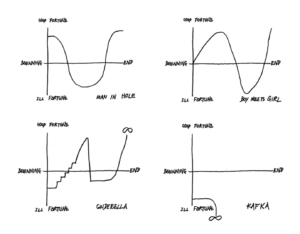

Kurt Vonnegut: The Shapes of Stories (apparently, the bottom left ‘Cinderella’ shape is the most popular structure in western culture).

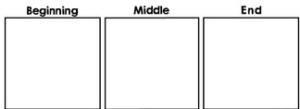

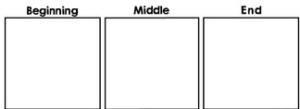

Ben Hale: The 3-9 Approach (this can be used across a whole book or applied to each scene or chapter).

Write a sentence summarising each stage of your novel (beginning, middle, end). Then write the sentence that comes before and after each stage. Each of the nine sentences should be important enough to be a fully-developed scene in the story. I’ve heard that it’s useful to think ‘and so/therefore/because of that…’ or ‘but’ between each section, rather than ‘and then…and then…and then…’ and to remember that each chapter should raise questions, answer some questions and leave some open, or raise more questions. Phew…so much to think about!

Genette and Chapman: Time-Led Plotting (this relates to the balance of story time versus text time, and affects pacing. ‘Story time’ is event length and ‘text time’ is how long it takes on the page).

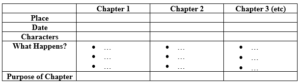

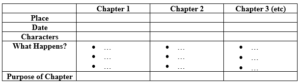

‘Flat Plan’: could be separated into scenes within chapters too, and other rows could be added, e.g. word count, how you want the reader to feel.

Experience

I used to be a total ‘pantser’, and I still wouldn’t consider myself a plotter, but I do now keep track of my chapters on a spreadsheet and try to fill in a little ahead, certainly (at the very least) the inciting incident, midpoint and ending, as well as creating a rough (very flexible/changeable) synopsis early on.

Points I’ve taken away from what I’ve learned about plotting are:

Final Thoughts

How do you plot, if at all?

Do you have any tips?

What are your strengths when it comes to plotting?

What are your weaker areas/what would you like to learn more about? Perhaps other Litopians can share their own tips and advice

---

Plotting

I’ve watched some great webinars on plotting recently and I thought I’d compile what I’ve learned, as much for myself as for anyone else who might find this info useful

The Four Cornerstones of Plot

- DESIRE – anything, as long as the character is passionate about getting it/there’s a sense of urgency/it can’t be ignored. Start with a ‘flawed want’, with the story leading to the realisation of the ‘what’s really good for them’ need.

- CONFLICT – delays the achievement of the desire (or may have led to the desire). It obstructs/complicates It should not be easy to resolve, e.g. a ‘rock and a hard place’ dilemma. There should be external AND internal/personal conflict. The inciting incident may be the worst thing that has ever happened to the character, but is ultimately beneficial to them. ‘Messes’ are often located at points of the inciting incident, the midpoint, and at the 80% mark. A satisfying ending has at least some resolution.

- CHOICE/S – characters must be active, not passive, agents, making decisions which lead to consequences (good or bad) and their own redemption (the latter shouldn’t just be down to circumstances!). Choices are where plot and character intersect. A character’s personal qualities/flaws can make a choice more difficult. Choices are difficult because of risk. They signify a point of no return.

- RISK – what is tangibly at stake for the protagonist? What will they lose if their choice backfires? What is the cost if a choice isn’t made?

Together, the Four Cornerstones Add Up to…

CHANGE!

A satisfying narrative arc portrays how protagonists change internally over time as a result of their choices. This change must be difficult – it must have cost the character something/involved a sacrifice/the ‘death’ of their former self. It must be irreversible. The change can be ‘heroic’ or ‘tragic’ (but a sub-plot/minor character’s change may be the opposite of the main plot/character’s change). Notably, the antagonist usually fails to change, and this is ultimately their most fatal flaw, whereas the protagonist’s eventual ability to change is their strength. A final point to emphasise is that the personal change/redemption matters more than the external/‘outer world’ resolution.

The Bestseller Code (Archer and Jockers)

The authors analysed the vocabulary of bestsellers, focusing on the words used to describe characters’ internal states (‘good’ times versus ‘bad’ times resulting from events). They concluded that a key commonality was regular reversals of fortune where turning points force the character to mobilise at the greatest points of conflict, make choices and risk something by making that choice. This is known as the ‘page-turner beat’. The graph shows the protagonist’s fortunes over time when compared to the ‘status-quo’ starting point.

One way to think of this is that the new conflict – resolution – new conflict – resolution sequence equates to the action – reaction – action – reaction sequence, equating to the external – internal – external – internal sequence.

Plot Structures

Kurt Vonnegut: The Shapes of Stories (apparently, the bottom left ‘Cinderella’ shape is the most popular structure in western culture).

Ben Hale: The 3-9 Approach (this can be used across a whole book or applied to each scene or chapter).

Write a sentence summarising each stage of your novel (beginning, middle, end). Then write the sentence that comes before and after each stage. Each of the nine sentences should be important enough to be a fully-developed scene in the story. I’ve heard that it’s useful to think ‘and so/therefore/because of that…’ or ‘but’ between each section, rather than ‘and then…and then…and then…’ and to remember that each chapter should raise questions, answer some questions and leave some open, or raise more questions. Phew…so much to think about!

Genette and Chapman: Time-Led Plotting (this relates to the balance of story time versus text time, and affects pacing. ‘Story time’ is event length and ‘text time’ is how long it takes on the page).

- Gap = fastest = no text, not much story time passes

- Summary = fast = little text, much story time passes

- Scene = real time = text time equals story time passing

- Dilation = slow = much text, little story time passes

- Pause = slowest = much text, no story time passes

‘Flat Plan’: could be separated into scenes within chapters too, and other rows could be added, e.g. word count, how you want the reader to feel.

Experience

I used to be a total ‘pantser’, and I still wouldn’t consider myself a plotter, but I do now keep track of my chapters on a spreadsheet and try to fill in a little ahead, certainly (at the very least) the inciting incident, midpoint and ending, as well as creating a rough (very flexible/changeable) synopsis early on.

Points I’ve taken away from what I’ve learned about plotting are:

- Don’t have a passive protagonist – give them agency.

- Raise the stakes – give the character difficult choices to make.

- Ensure they change/grow between the beginning and the end. Shift from what they ‘want’ to what they really ‘need’.

- A page-turner includes regular reversals of fortune.

- My current work-in-progress matches Vonnegut’s Cinderella

- Drive the narrative by thinking ‘and so/therefore/because of that…’ or ‘but’ between each section, rather than ‘and then…and then…and then…’

- Each scene/chapter should have a purpose/move the story forward/cause a shift in the character’s relationship to their desire/goal, either positively or negatively.

- My Achilles Heel is to summarise (‘tell’) rather than ‘show’ a scene in ‘real time’. Note to self: if it’s important enough to show as a curve/turning point on the story graph, it deserves to be written out as a fully-fleshed scene!

Final Thoughts

How do you plot, if at all?

Do you have any tips?

What are your strengths when it comes to plotting?

What are your weaker areas/what would you like to learn more about? Perhaps other Litopians can share their own tips and advice

---

* Like this post? Please share here

* Start your own blog here